The hidden harm of restrictive practices lies not only in the control they impose, but in the infringement on human rights, the loss of freedom, and the quiet suppression of a person’s dignity.

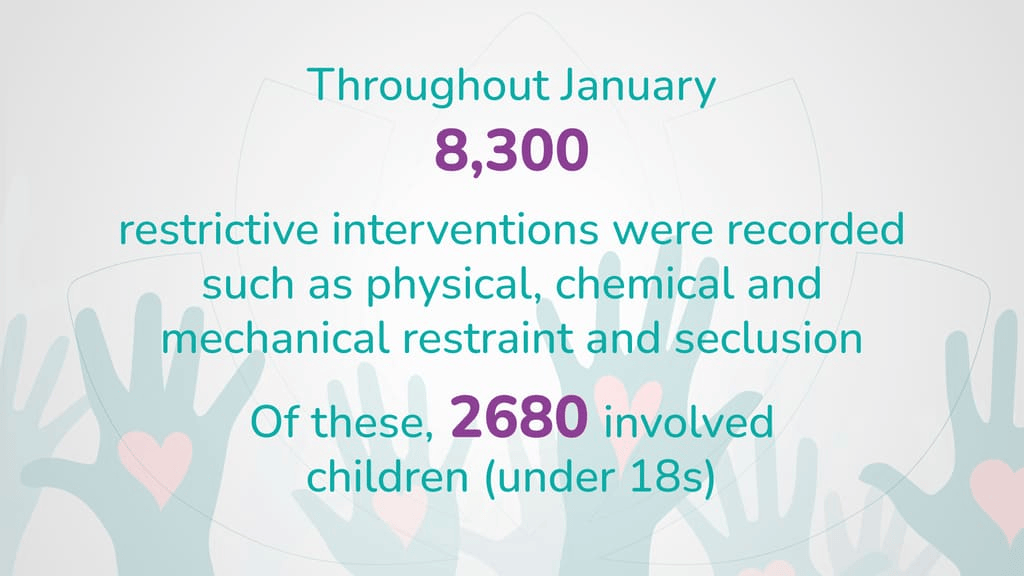

According to the latest NHS report, by March 2025, over 8,000 people had been subjected to restrictive practices- among them, 2,000 were children under the age of 18. The group of people affected include autistic people, people with learning disabilities and mental ill health.

Ongoing inquiries into the harm experienced by people in health and care settings have highlighted that restrictive interventions can pose serious risks to the people who may be unable to keep themselves safe because of their care and support needs. Under the Care Act 2014, local authorities and mental health services have responsibilities to safeguard people who may be at risk of harm or abuse of any kind.

What Are Restrictive Practices?

Restrictive practice refers to any action that forces people to do something against their will, prevents them from doing something they choose to do, limits their freedom, or involves restraining or depriving them of their liberty.

Restraint, seclusion, and segregation are widely recognised as the more obvious and extreme forms of restrictive practice. However, there are quieter, everyday restrictions that can easily become routine- often in response to perceived risks, time pressures, or staffing limitations.

These might include things like stopping someone from making a hot drink after a certain hour, or limiting access to friends, visitors, or even food- not because it’s in the person’s best interest, but because there aren’t enough people around to support them.

In every setting, care should be shaped around the person- by listening, understanding how they communicate, and responding in ways that respect their experiences and needs. This understanding should lead to adjustments that make restrictive practices unnecessary.

There are times when restrictions may be considered, but only when they meet clear criteria: they must be legally justified, clearly aimed at a legitimate purpose, and used in the least restrictive way possible, always with people’s rights at the centre.

‘I was put in a secure room because they didn’t know what else to do with me’. -Quoted in research presented by Dr. Ada Hui, Assistant Professor and Deputy Director of Postgraduate Research, University of Nottingham, highlighting the lived experience of a person admitted to hospital.

Restrictive Practices and the Mental Health Act

The use of restrictive practices within the framework of the Mental Health Act raises important questions about the balance between safety and human rights. While the Act allows for certain restrictions, such as physical restraint and seclusion, these should only be applied when absolutely necessary, usually to prevent harm to the person or others.

However, these practices can have lasting psychological and physical consequences, contributing to feelings of powerlessness, mistrust, and trauma. The real challenge is ensuring that restrictive practices are used sparingly and ethically, in line with the principles of the Mental Health Act, which prioritises dignity, respect, and the least restrictive option possible. Ongoing assessment and careful oversight are essential to protect people’s’ rights while addressing their immediate needs.

Harms of Restrictive Practices

Every kind of restrictive intervention can have serious consequences for people’s health and overall well-being. Recently, Dr. Ada Hui, Assistant Professor and Deputy Director of Postgraduate Research University of Nottingham, conducted research on the inequalities and the use of restrictive practices.

The research explored the lived experiences of people in a high-security hospital, highlighting current challenges around least restrictive practices, organisational culture, role, identity, and the sense of belonging. The research examines the significant impacts of restrictive practices on people’s overall functioning, which are discussed below.

Impact on People’ Identity

Restrictive practices often discredit multiple aspects of a person’s identity, adding layers of psychological harm that go beyond the immediate interventions. People, in an effort to avoid restrictive measures or to gain discharge, may present as emotionally well, masking their true distress.

This disengagement, driven by fear, escalates over time, leading to the labelling of perfectly natural reactions as ‘challenging behaviors.’ The consequence is not just increased coercion and control but the deepening of mistrust, as their experiences and needs are dismissed or discredited.

This cycle not only intensifies the fear and anxiety already present but also inflicts serious harm, creating lasting challenges in how a person sees themselves and relates to the world inside and outside the hospital. These initial and recurring struggles shape their identity in ways that can be difficult to heal, especially when their voice is lost in the system.

In an effort to avoid restrictive interventions or to secure a quicker discharge from the hospital, many people tend to present as emotionally well, even when they are not.

Psychological Harm

The psychological harm of restrictive practices runs deep, often leaving people with lasting trauma that affects their ability to feel safe, heard, or even human. Many people describe feeling dehumanised, silenced, and powerless, especially when restrictive measures are used without genuine understanding or trauma-informed care.

Over time, these experiences can cause long-term psychological damage and create new barriers to recovery, safety, and trust. The impact goes beyond the immediate moment, leading to feelings of fear, humiliation, and distress that can endure long after the intervention has ended.

Some of the serious psychological consequences include:

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): Repeated or intense experiences of restraint can mirror earlier trauma, or become traumatic in themselves.

- Heightened Anxiety and Panic: The unpredictability of interventions and the fear of being restrained again often lead to persistent anxiety.

- Depression and Hopelessness: Feeling unheard or controlled can lead to a loss of autonomy, identity, and self-worth.

- Disengagement from care: Many people begin to mask their distress to avoid being restrained, leading to withdrawal and missed support.

- Distorted self-perception: Being labelled as ‘challenging’ reinforces stigma, leaving people to internalise a negative view of themselves.

- Loss of trust in services: Repeated restrictive practices can damage therapeutic relationships, leading people to avoid or fear future care.

- Feelings of fear, humiliation, and distress: The immediate emotional impact of restrictive practices can cause long-lasting shame and a sense of vulnerability.

Physical Harm

The long-term stress and trauma from restrictive practices can lead to serious health conditions like heart disease, diabetes, and even cancer. The constant anxiety and fear experienced during such interventions raise stress hormones, resulting in higher blood pressure, weakened immune systems, and metabolic imbalances. Additionally, the psychological impact of these practices often leads to unhealthy coping mechanisms, such as poor diet or lack of exercise, further compounding the risk of chronic health issues.

- Chronic Health Conditions: Long-term stress from physical restraint can increase the risk of heart disease, diabetes, and cancer.

- Elevated Stress Hormones: Fear and anxiety raise stress hormones, contributing to high blood pressure and weakened immunity.

- Metabolic Imbalances: Stress from restrictive practices disrupts metabolism, affecting overall health.

- Unhealthy Coping Mechanisms: The psychological toll often leads to poor eating habits and inactivity, further increasing health risks.

- Increased Risk of Self-Harming Behaviours: Emotional strain may contribute to self-harming behaviours as a form of coping.

- Weakened Immune System: Chronic stress can impair the immune system, making individuals more vulnerable to illness.

Declining Trust in Mental Health Care

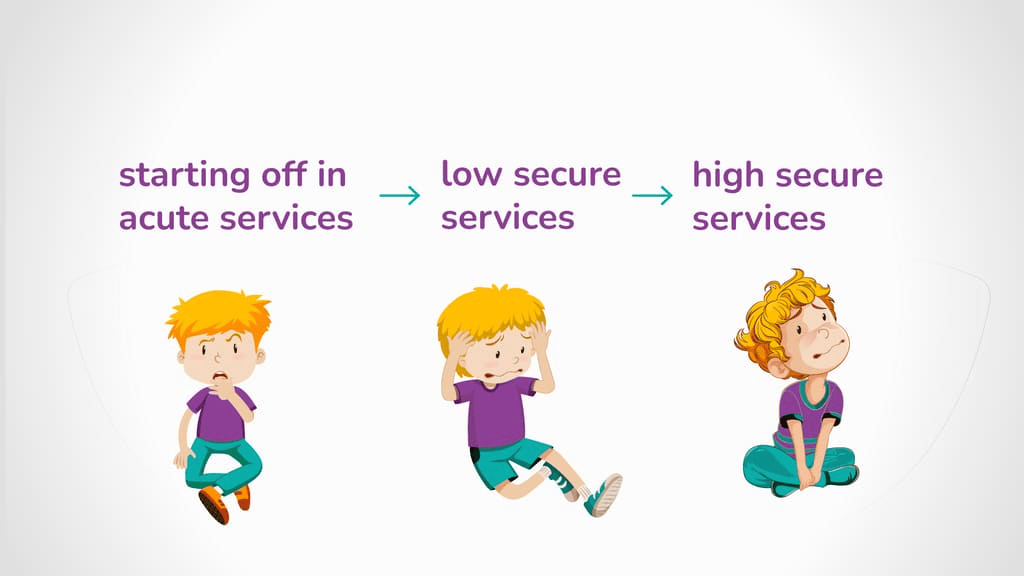

Dr. Ada Hui’s research found that for many people, the journey through mental health services begins in acute settings, moving through low and ending up in high-secure services. The process creates a cycle of fear and distrust. With each restrictive intervention, there is a significant reinforcement of the cycle of fear and distrust. Within hospital walls, people often face heightened coercion and prolonged use of restrictive practices.

Human Rights Concerns

Every restrictive intervention must be treated as an absolute last resort- used only when it is truly unavoidable, and only to ensure the immediate safety and wellbeing of the person. Anything less risks undermining people’s human rights.

A person-centred approach places human dignity at the heart of care. It means asking not just what needs to be done, but why– and whether there is another way. When restrictions become routine, or are applied without thoughtful reflection, the risk is not just harm, but a denial of autonomy, voice, and freedom. Human rights in care settings aren’t abstract ideals- they’re lived, experienced, and must be protected in every decision made.

Alternatives to Restrictive Practices

When proactive strategies are embedded into everyday support- grounded in understanding what a person needs, wants, or what makes them feel distressed- the need for restrictive interventions can often be avoided altogether. Least restrictive and non-restrictive approaches focus on building trust and connection, not control, allowing reactive responses that uphold safety, dignity, and a person’s freedom.

Trauma-Informed Care

Trauma-informed care recognises that many people have lived through distressing experiences that continue to shape how they respond to the world. Trauma-informed care plans are built with this in mind- focusing on emotional safety, trust, and choice. By understanding a person’s history, what helps them feel safe, and what may trigger distress, support can be shaped in ways that avoid retraumatisation and reduce the need for restrictive practices.

Proactive Approach

Proactive support is rooted in the idea that it’s always better to prevent than to heal. By focusing on early intervention and understanding a person’s needs before distress even occurs, we can significantly decrease the risk of challenging behaviors and the need for restrictive practices. A proactive approach not only creates safer environments but also promotes trust, dignity, and long-term well-being. Key components of this approach include:

- Positive Behaviour Support (PBS): Understanding the function behind behaviors and developing strategies that promote positive outcomes.

- PROACT-SCIPr®: A structured, person-centred framework that emphasises proactive, non-restrictive interventions to prevent escalation and enhance safety.

Together, these approaches help reduce the reliance on restrictive practices and ensure care is tailored to each person’s unique needs.

De-escalation Techniques

When a crisis has already occurred, de-escalation techniques are crucial in regaining calm and preventing further escalation. The goal is to connect with the person, build trust, and create a safe space for them to regain control.

This might involve reading body language to understand their emotions, offering them some time alone in their personal space to decompress, or speaking in a calm, non-threatening manner. Giving them space and showing empathy can help lower their stress and provide the opportunity for them to feel heard, ultimately reducing the need for restrictive interventions.

Restriction Reduction Plans

Restriction Reduction Plans are comprehensive, individualised strategies designed to minimise and, where possible, eliminate the use of restrictive practices in care services. These plans are developed collaboratively, involving the person receiving care, their support network, and healthcare professionals, ensuring that interventions are tailored to individual needs and preferences.

Key components include:

- Personalised Assessment: Identifying underlying causes of distress through thorough evaluations, which may involve understanding personal triggers, environmental factors, and past experiences.

- Person-Centered Planning: Developing care plans that prioritise the individual’s rights, preferences, and goals, fostering a sense of ownership and empowerment in their care journey.

- Positive Behavior Support (PBS): Implementing proactive strategies that focus on teaching and reinforcing positive behaviors, thereby reducing the likelihood of crisis situations.

- Staff Training and Development: Equipping staff with the skills and knowledge to recognise early signs of distress and respond appropriately, emphasising de-escalation techniques and empathetic communication.

- Continuous Monitoring and Evaluation: Regularly reviewing and adjusting the plan based on feedback and observed outcomes, ensuring that strategies remain effective and aligned with the individual’s evolving needs.

By integrating these elements, Restriction Reduction Plans aim to create a therapeutic environment that respects individual autonomy and promotes recovery, aligning with contemporary mental health care standards that emphasize dignity and human rights.

PROACT SCIPr® and Positive Behaviour Support

PROACT SCIPr® is a structured approach that guides carers and professionals in providing non-restrictive, person-centred care. It emphasises reducing distress through de-escalation techniques, offering tailored support based on each person’s needs, and fostering safety through clear, collaborative strategies. This approach empowers staff to act in ways that promote safety without resorting to physical restraint or isolation.

Positive Behaviour Support (PBS), on the other hand, takes a holistic view of an individual’s behaviour, seeing it as communication rather than something to be controlled. PBS focuses on enhancing quality of life and teaching new skills that can reduce the likelihood of challenging behaviours. By understanding the person’s needs, preferences, and triggers, PBS practitioners work towards creating environments that allow people to thrive with dignity and respect.

When combined, PROACT SCIPr® and PBS ensure that support is both effective and compassionate, focusing on prevention rather than reaction. Through these frameworks, restrictive practices become less necessary, as the primary goal shifts to understanding, teaching, and empowering people to live fulfilling lives free from unnecessary constraints.

Advocacy & Change

Turbulent journeys through systems meant to care can leave people carrying the weight of quiet, lasting harm- whether living through restrictions or supporting someone through them. The emotional labour is real, and so is the sense of injustice when care becomes something people are done to, not done with. Behind every locked door is a person’s story- where risk is placed above rights, and safety is shaped more by fear than understanding.

Catalyst Care Group Advocates for Reducing Restrictive Practices

At Catalyst Care Group, our policy is built on a people-first, whole-centred approach that prioritises the human rights model of care. We ensure the right staff are matched to each person, particularly during moments of crisis, by implementing proactive and least restrictive support strategies to keep people safe.

Using Positive Behaviour Support (PBS) strategies, our team is equipped to manage crises effectively, support smooth transitions, and reduce the need for hospital admissions. As a certified PROACT SCIPr® training centre, we ensure our staff have the skills to offer thorough and compassionate support to people with behaviours of concern.

To further reduce the reliance on restrictive practices, we offer a variety of specialised services, such as occupational therapy, mental health, and Talking Mats and multimedia support.

Working together with our multidisciplinary team of PBS specialists, community psychiatric nurses, and the Restraint Reduction Network, we strive to achieve the best possible outcomes for individuals. Our approach includes:

- Conducting functional and intentional assessments of behaviours of concern

- Developing evidence-based support strategies

- Providing regular, personalised training for support teams

- Creating tailored PBS plans to support person’s mental health

- Engaging in collaborative, multidisciplinary efforts

- Offering emotional support and encouraging open dialogue with our support workers

For more information, contact us today!