In places meant to heal, trauma should not be part of the treatment.

Although restraints are often introduced to manage risk, they can unintentionally cause serious psychological harm. In environments that are meant to feel safe, this harm is often described as “sanctuary trauma.” Research increasingly shows that restraint can be a direct contributor to PTSD, highlighting an urgent need for safer alternatives and trauma-informed practices that protect emotional safety, dignity, and long-term mental well-being.

Restraint may be intended for safety, but it can affect well-being and fundamental human rights, leading to trauma responses that persist over time.

What Are Physical Restraints

Physical restraints refer to the use of physical force, devices, or materials to restrict a person’s movement or access to their own body. In healthcare and crisis settings, this can include being physically held by using restrictive tools, sometimes alongside medication used to manage behaviour. These measures are typically intended to reduce the immediate risk of harm to the person or others.

Common physical restraints include:

- Mechanical / Equipment: The use of physical devices such as bed rails, lap belts, wrist or ankle mittens, and specialist chairs with fixed tables.

- Manual / Physical: Situations where staff physically hold a person or restrict their movement using their own bodies.

- Pharmacological (Chemical): The use of medication primarily to manage or control behaviour rather than to provide therapeutic treatment, often alongside physical restraint.

UK government guidance and NHS frameworks stress that physical restraint should be used only as a last resort because it carries risk of physical injury and psychological distress, and that efforts should focus on reducing restrictive practices and increasing de-escalation.

Physical Restraints in Mental Health Care

In UK mental health settings, restrictive practices, including physical restraint, seclusion, and rapid tranquillisation, are still used to manage situations of perceived risk, despite clear policy guidance that they should be avoided wherever possible.

NHS data show wide variation in the use of restraint across mental health settings, with thousands of restraint incidents recorded each year, particularly in inpatient wards, and higher rates affecting people who are detained under the Mental Health Act, people from ethnic minority backgrounds, and people with learning disabilities or autism.

When a loved one is facing restrictive interventions, understanding their rights can help families know what to expect and what support should be in place. Below is a brief summary of the Use of Force Act, designed to help families understand what protections are in place and how dignity and autonomy should be maintained in times of crisis.

Use of Physical Restraints and Restrictive Practices

Physical restraints and restrictive practices may be used in health and social care settings only when there is an immediate and serious risk of harm to a person or to others, and when all less restrictive options have been exhausted. Their purpose is to manage acute situations where safety cannot be maintained through de-escalation or supportive approaches alone. However, because these interventions limit freedom and autonomy, their use must always be exceptional, proportionate, and time-limited.

The latest NHS data recorded 8,300 restrictive interventions in a single month, including physical, mechanical, and chemical restraints, as well as the use of isolation. Of these incidents, 2,680 involved children.

All health and social care organisations, across both public and private sectors, are required to actively reduce reliance on restrictive practices. When restraint is unavoidable, decisions must be guided by human rights, with careful consideration of dignity, choice, and well-being before any action is taken. This approach recognises the context of each care setting while prioritising the safety of the person, those around them, and the people providing care.

Care Quality Commission (CQC) states that restraint must be lawful, necessary, and proportionate, and highlights that misuse or overuse may breach Human Rights Act 1998 protections, particularly the right to liberty, dignity, and freedom from degrading treatment.

(CQC guidance)

Physical and Psychological Harms of Restraints

Qualitative UK research with young people in inpatient mental health services describes restraint as emotionally traumatic, with distress that begins before physical contact and continues long afterwards, which is consistent with processes seen in PTSD development.

A systematic review (largely drawing on psychiatric inpatient data) reported rates of post-traumatic stress symptoms between 25 % and 47 % among people following restraint and seclusion events, indicating substantial psychological harm associated with these practices.

Common physical or psychological harm caused by physical restraint use includes:

- Physical pain, injury, or breathlessness during restraint, sometimes leaving lasting physical effects

- Fear and panic that can feel overwhelming and impossible to escape

- A sudden loss of control that can be deeply frightening

- Feeling powerless, trapped, or ignored in moments of extreme distress

- Memories of restraint that return long after, through flashbacks, nightmares, or intrusive thoughts

- Anxiety that lingers, making everyday situations feel unsafe

- Loss of trust in carers, services, or environments that are meant to provide care

- Feelings of shame, humiliation, or being treated as a problem rather than a person

- Re-awakening of past trauma, especially for people with previous difficult experiences

- Long-term emotional impact that can affect confidence, relationships, and willingness to seek help

Healthcare professionals have a legal and ethical considerations to use proactive strategies to reduce physical restraint.

How Do Restraints Affect Cognitive and Mental Health?

Restraints can affect cognitive and mental health in ways that go far beyond the immediate incident. Research and national guidance recognise that restrictive and coercive practices can be experienced as traumatic, leaving some people with ongoing anxiety, low mood and depressive symptoms, and a heightened sense of threat that can persist after discharge.

In inpatient and crisis care settings, restraint has also been linked with delirium-an acute state of confusion that is itself associated with poorer longer-term cognitive outcomes-and with wider physical outcomes such as longer ventilation time and reduced physical recovery in the months that follow.

Some of the effects, but not limited to, include:

- Impaired attention and concentration, often following high stress and fear during restraint

- Memory disruption, including fragmented or intrusive recall of the restraint event

- Reduced executive functioning, affecting planning, judgement, and decision-making

- Acute confusion or delirium, particularly in inpatient, older adult, or critical care settings

- Slower cognitive processing, linked to heightened stress responses and physiological arousal

- Increased anxiety, including hypervigilance and constant threat perception

- Depressive symptoms, such as low mood, withdrawal, and reduced cognitive motivation

- Post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSD), which can further impair memory, focus, and emotional regulation

- Difficulty learning or engaging in therapy, due to reduced cognitive trust and psychological safety

- Long-term impact on cognitive confidence, affecting independence, problem-solving, and engagement with care

Alongside these cognitive and physical outcomes, evidence from psychiatric settings suggests post-traumatic stress symptoms after restraint/seclusion, particularly where there is prior trauma, reinforcing why UK frameworks emphasise prevention, de-escalation, and minimising restrictive practice wherever possible.

Definition of PTSD

Post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) occurs when a person experiences or witnesses a deeply terrifying event- trauma. It can happen to anyone and usually presents with symptoms like intrusive memories or flashbacks, nightmares, heightened anxiety or alertness, emotional distress, and avoidance of reminders of the trauma – often affecting everyday life, relationships, and the ability to feel safe, connected, and supported by the people around them.

However, this is just part of the PTSD symptomatology. Although it mainly depends on the traumatic experience and other social-biological factors, PTSD may include intense psycho-somatic symptoms that may interfere with people’s daily life and functioning.

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms

Common symptoms of PTSD can affect thoughts, emotions, the body, and everyday life. They may appear soon after a traumatic event or develop over time, and they can look different from person to person.

- Intrusive memories – unwanted thoughts, flashbacks, or reliving the event

- Nightmares or disturbed sleep, often linked to the trauma

- Heightened anxiety or constant alertness, feeling on edge or easily startled

- Avoidance – trying to stay away from reminders, places, people, or conversations

- Emotional distress – fear, anger, guilt, shame, or feeling overwhelmed

- Low mood or depressive symptoms, including withdrawal or loss of interest

- Difficulty concentrating or remembering things

- Strong physical reactions, such as a racing heart, sweating, or shortness of breath

- Changes in trust and relationships, including feeling disconnected from others

- Feeling unsafe, even in calm or familiar environments

For families, these symptoms can be confusing and worrying to witness. PTSD is not a choice or a weakness-it is a natural response to experiences that overwhelm a person’s sense of safety and control.

Psychosomatic Symptoms Linked to PTSD

PTSD often affects the body as much as the mind. Trauma can keep the nervous system in a constant state of alert, leading to physical symptoms with no clear medical cause.

- Chronic muscle tension, aches, and unexplained body pain

- Headaches or migraines, often frequent or persistent

- Gastrointestinal problems, including nausea, stomach pain, bloating, diarrhoea, or constipation

- Chest pain or tightness, sometimes mistaken for heart problems

- Shortness of breath or rapid breathing, especially during stress

- Racing heart or palpitations, linked to heightened fight-or-flight response

- Dizziness, light-headedness, or feeling faint

- Fatigue or exhaustion, even after rest

- Sleep disturbances, including insomnia, restless sleep, or waking unrefreshed

- Heightened pain sensitivity, where normal sensations feel intense or unbearable

- Trembling, shaking, or internal restlessness

- Sweating or temperature dysregulation

- Jaw clenching or teeth grinding

- Appetite changes, including loss of appetite or overeating

- Weakened immune response, frequent infections or slow recovery

- Skin reactions, such as rashes, itching, or flare-ups of existing conditions

Who May Be at Risk of Developing PTSD?

People can respond very differently to trauma, but some are more vulnerable to developing PTSD, particularly when distress is intense, repeated, or unsupported. Those at higher risk may include:

- Children and young people, whose brains and coping skills are still developing

- People who experience physical restraint, coercion, or loss of control, especially in care or crisis settings

- People with previous trauma, including abuse, neglect, violence, or medical trauma

- People with existing mental health difficulties, anxiety, or depression

- People with learning disabilities or autism, particularly when communication needs are not understood

- People exposed to repeated or prolonged traumatic events, rather than a single incident

- People who feel powerless, frightened, or unheard during the event

- People who lack emotional support afterwards, including family, carers, or trusted professionals

- Families and carers, who may develop secondary or vicarious trauma after witnessing distress

PTSD Among People with Mental Health Challenges

People who live with ongoing mental health challenges are more likely to be affected by experiences that feel intense, frightening, or uncontrollable. When distress is already present, adverse events such as crises, admissions, or restrictive interventions can have a deeper impact and may increase the likelihood of PTSD developing.

For example, a person who is already struggling with anxiety or psychosis may experience a crisis admission as frightening and disorienting; if physical restraint is used during that admission, the loss of control and fear can become the strongest part of the memory, increasing the risk of PTSD rather than helping the person feel safe.

The Link Between Physical Restraints and PTSD

Physical restraints, particularly in healthcare or crisis settings, are strongly linked to the development of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Being physically restrained can overwhelm people with fear, helplessness, and a sudden loss of control. For many children and adults, this experience does not fade once the restraint ends.

Instead, it can lead to PTSD symptoms such as intrusive memories, nightmares, heightened anxiety, and constant hyper-alertness. Trust in caregivers may be damaged, and for people with existing trauma, restraint can intensify distress and behaviours rather than reduce them.

What are the Potential Long-term Psychological Consequences?

Physical restraints can be a direct cause of PTSD. Even a single incident may leave a lasting psychological imprint, changing how a person experiences safety, control, and trust. When restraints are used repeatedly, the impact can deepen over time, increasing emotional distress and, in some cases, contributing to self-harm. Repeated experiences of restraint can also alter how a person sees themselves, undermining identity, self-worth, and confidence, leaving a lasting negative effect on self-perception.

Physical Restraints as a Trigger for PTSD

Physical restraints are recognised risk factors for re-traumatisation and can act as powerful triggers for people living with PTSD. As adverse events, they can re-evolve fear, loss of control, and past traumatic memories, often intensifying symptoms rather than reducing distress. Effective care, therefore, must be focused on proactive support, where the risk of trauma and fear should be kept to a minimum.

Alternatives to Physical Restraints

When the care and support plan is created based on the person’s unique needs, aims, strengths and challenges, challenging behaviours are significantly reduced. This involves proactive care focused on prevention rather than reaction.

Instead of relying on restrictive practices, positive approaches focus on understanding, prevention, and meaningful support. They aim to build trust, reduce distress, and create safer, more empowering environments for everyone involved.

Proactive Support

Instead of responding only after a crisis occurs, proactive support identifies needs early. It focuses on noticing subtle signs of distress, adjusting the environment, and offering reassurance before situations intensify. By doing so, it helps people feel safer and better understood, making crisis situations less likely to develop.

Strengths-Based Approach

A strengths-based approach centres on a person’s abilities rather than their limitations. It acknowledges skills, interests, and potential, using these as the basis for support and progress. By valuing what people can do, it supports confidence and a more positive sense of self.

Positive Behaviour Support (PBS)

Positive Behaviour Support (PBS) focuses on understanding the reason behind behaviour, not just the behaviour itself. It helps identify triggers and supports people to communicate their needs in safer, more effective ways, with the aim of improving everyday life rather than simply stopping behaviours.

By embedding trauma-informed and neurodiversity-sensitive practices, PBS promotes a holistic understanding of each person, reduces the need for physical interventions, and supports people to lead more independent, empowered lives.

PROACT-SCIPr-UK®

PROACT-SCIPR-UK® is a therapeutic, values-based approach that supports autistic people, people with a learning disability, and/or mental health needs. It focuses on the whole person and uses proactive strategies to reduce distress, crisis escalation and the need for crisis intervention.

Relying on least restrictive practices, the approach promotes consistency, dignity, and respect – enabling people to feel safe, heard, and in control of their own lives.

Importance of Reducing Restrictive Practices in Health and Social Care

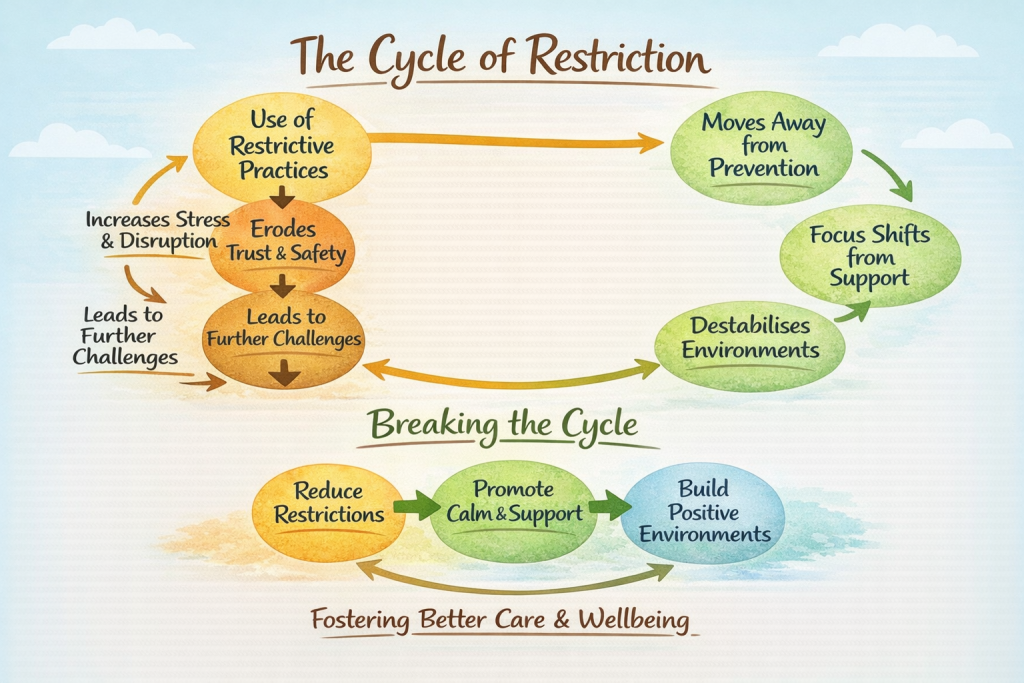

The use of restrictive practices can set off a chain of negative consequences that go far beyond the immediate incident. Rather than restoring stability, restriction can increase distress, damage trust, and lead to further crises, creating a cycle where more control is used to manage the impact of previous restraint.

Over time, this can destabilise care environments, place greater strain on staff and services, and shift focus away from prevention and support. Reducing restrictive practices helps break this cycle, supporting calmer settings, safer relationships, and more sustainable care systems built on understanding rather than control.

Catalyst Care Group is Dedicated to Reducing Restrictive Practices

At Catalyst Care Group, care begins with people. Our approach supports the whole person and is grounded in a human-rights-led model of care. We take care to match the right staff to each person, particularly during moments of heightened distress, and focus on proactive, least restrictive approaches that promote safety, trust, and dignity.

By using Positive Behaviour Support (PBS) strategies, our team supports people through crises, manages transitions, and helps prevent avoidable hospital admissions. Support workers are trained in PROACT-SCIPr, a structured and compassionate approach that emphasises safety, understanding, and human connection when behaviours of concern arise.

Support plans are carefully developed with a strong focus on proactive strategies and positive reinforcement, reducing reliance on reactive responses and physical restraint use wherever possible. The aim is to respond early, maintain dignity, and support emotional wellbeing before situations escalate.

Working within a multidisciplinary team-including PBS specialists, speech and language therapists, and community psychiatric nurses-we work closely with the Restraint Reduction Network, demonstrating a clear commitment to reducing restraint and improving care outcomes through:

- Conducting functional and intentional assessments of behaviours of concern

- Developing evidence-based, person-centred support strategies

- Creating personalised PBS plans

- Providing regular, tailored training for support teams

- Working collaboratively across disciplines and services

- Supporting reflective practice through open conversations and emotional support for staff

For more information, contact us today!