We all have different perspectives on how we see and experience the world around us.

For many people, a change in routine or a daily task feels perfectly normal. For others, it can bring distress, anxiety, and disruption to daily life. When we have our brains wired differently, and that neurological difference affects the way we live, we are talking about neurodiversity.

Is OCD neurodivergent?

Among the many forms of neurodivergence, Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is considered as one that affects how people process thoughts, manage routines, and respond to uncertainty.

An estimated 750,000 people aged 16–64 in the UK are currently living with OCD. Despite how common it is, many people still struggle in silence, often feeling misunderstood or unsure where to turn for help.

The Origin and Evolution of Neurodiversity

Neurodiversity describes the natural differences in how people’s brains work and interpret the world. These variations shape how we think, learn, communicate, and interact. Autism, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder ADHD, dyslexia, and OCD are all part of this spectrum-ways of experiencing life that may differ from what’s considered typical but are equally valid.

The idea of neurodiversity emerged in the mid-1990s, with the start of Autism Network International. Sociologist Judy Singer was the first to introduce the term, inspired by early advocates such as Jim Sinclair, who emphasised that autism is not something to be cured but a different way of being.

Over time, the concept has grown to include a wider range of neurological differences, including:

- Autism spectrum disorder

- ADHD

- Dyslexia

- Tourette Syndrome

- Learning disabilities

- Dyslexia

- Dyspraxia

- Dyscalculia

- Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD)

- Sensory Processing Disorder

Today, the neurodiversity movement continues to promote acceptance, equity, and meaningful accommodations-shifting the focus from deficit to diversity.

Defining OCD

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) involves recurring, intrusive thoughts or fears-known as obsessions-that lead to repetitive behaviours called compulsions. These patterns can disrupt daily life and cause considerable emotional distress.

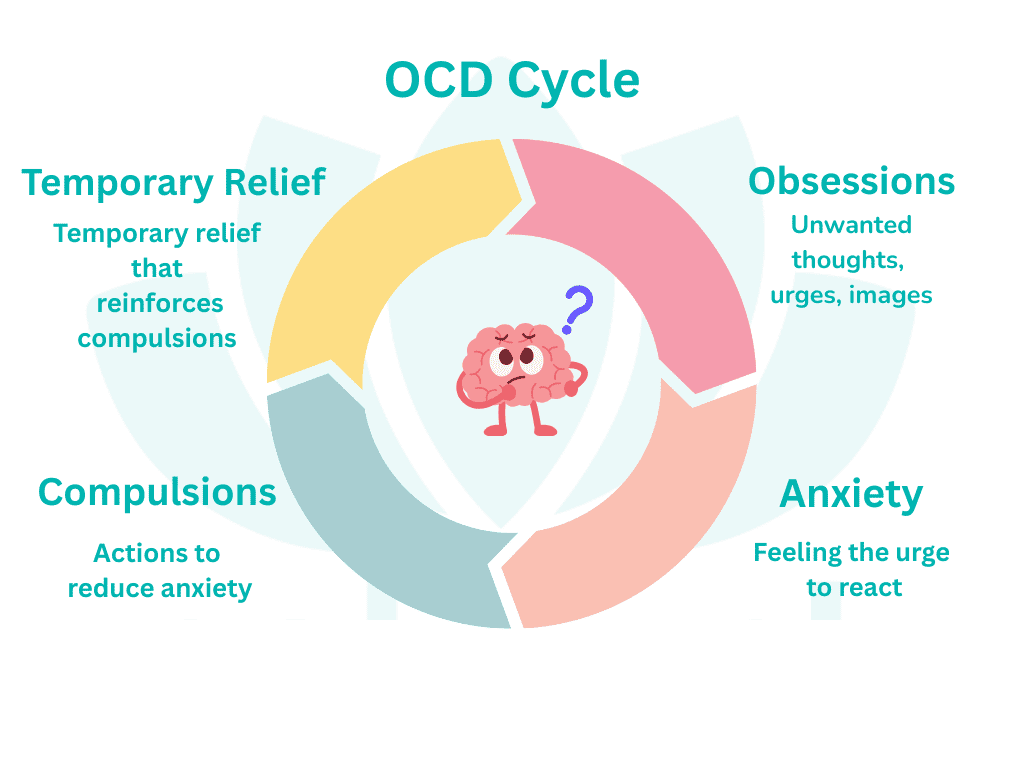

People often feel compelled to perform certain actions to relieve anxiety or discomfort caused by these intrusive thoughts. Even when trying to resist or ignore them, the thoughts usually return, creating a cycle of repetitive behaviours.

OCD typically revolves around specific themes, such as an excessive fear of contamination. For example, someone may repeatedly wash their hands to the point of irritation in an effort to feel clean or safe.

Key Characteristics

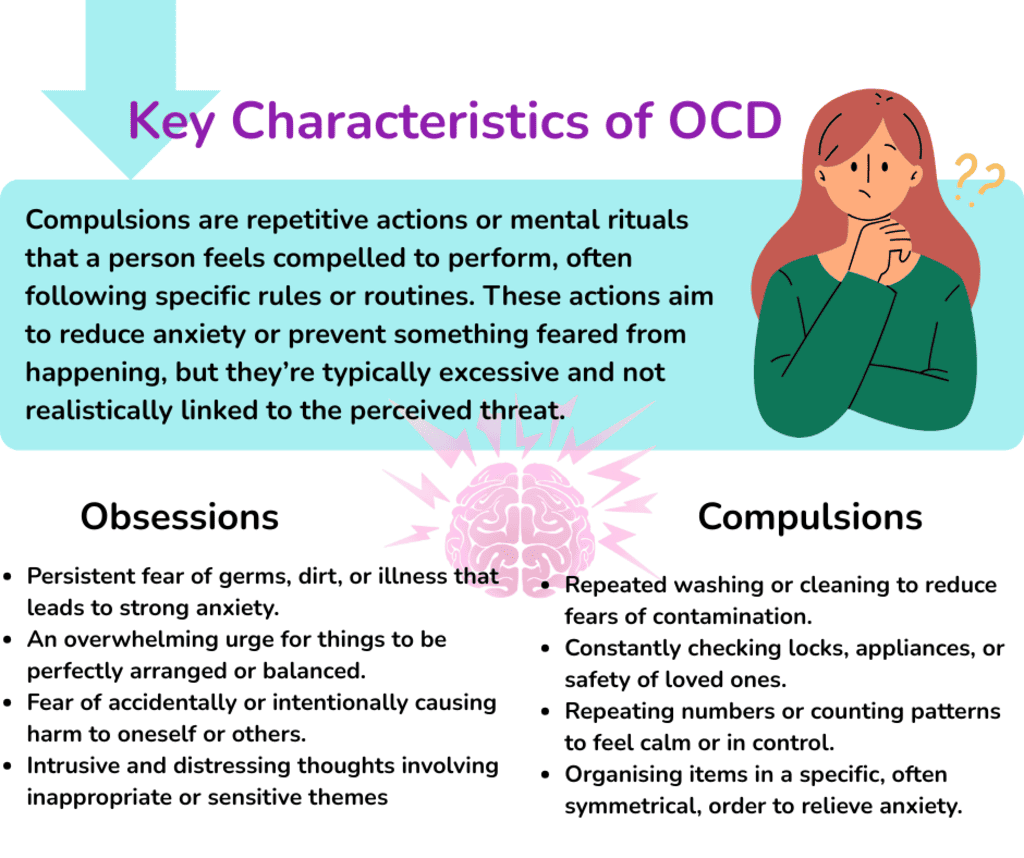

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is characterised by recurring obsessions-unwanted thoughts, images, or urges-and/or compulsions, which are repetitive actions or mental rituals carried out to ease the anxiety those thoughts create. These patterns can take up considerable time and cause distress or difficulties in daily life.

Common obsessions might involve worries about contamination, a strong need for order or symmetry, or intrusive thoughts about harm, while compulsions often include behaviours such as checking, cleaning, or arranging things repeatedly.

Common OCD symptoms often include:

- Obsessions are intrusive, unwanted thoughts, images, or urges that repeatedly enter a person’s mind and cause distress. These can include fears of contamination, intrusive sexual or aggressive thoughts, or a need for order and symmetry.

- Compulsive behaviours are repetitive actions or mental rituals carried out in response to these obsessions. They are often performed to reduce anxiety or prevent something bad from happening. Examples include excessive hand washing, checking locks, counting, or arranging objects in a specific way.

- Cycle: The relief brought by compulsive behaviour is usually short-lived. Soon after, the obsessive thoughts return, triggering anxiety again and continuing a difficult cycle of obsessions and compulsions.

- Impairment: This ongoing cycle can become time-consuming-often taking more than an hour each day-and may cause significant distress or disruption in daily routines, relationships, work, or education.

Is OCD Considered Neurodivergent?

Within clinical discussions, opinions vary on whether OCD should be seen as a form of neurodivergence.

Research in recent years has shown that OCD has neurological roots – meaning it’s linked to how the brain and nervous system function. Studies have found that people living with OCD often show differences in brain activity and structure, suggesting their brains work in unique ways. Because of this, some researchers and clinicians view OCD as part of the neurodivergent spectrum.

Still, whether OCD is considered neurodivergent isn’t only a scientific discussion – it’s also about perspective. It depends on how we define neurodivergence itself. If we understand it as including any difference in how the brain processes information, then OCD could certainly be seen as one expression of neurodivergence.

Where Do OCD and Neurodiversity Intersect?

OCD and neurodiversity often meet at the point where minds work a little differently-where patterns, sensitivities, and ways of thinking shape how people experience the world. Many of these experiences overlap: repetitive behaviours, sensory differences, and challenges with flexibility or social connection.

Although professionals may describe OCD in different ways, many people who live with it feel it belongs within the broader neurodivergent community. It reflects both the way their brains are wired and how those differences become part of who they are.

Neurological and Cognitive Connections

Brain differences:

Research shows that OCD is rooted in the brain, with differences in how certain areas communicate and function. These patterns often resemble those seen in other neurodivergent conditions like autism and ADHD.

Repetitive and ritualistic behaviours:

Routines and rituals can bring comfort, predictability, or a sense of control. This is something that people with OCD often share with others who are neurodivergent, such as those on the autism spectrum.

Sensory experiences:

Many people with OCD notice the world in intense ways—sounds, textures, or sensations that others might overlook can feel overwhelming. These sensory differences often mirror the experiences of autistic people.

Cognitive rigidity:

Adapting to change or shifting thought patterns can be difficult. This challenge with flexibility is another shared trait between OCD and other forms of neurodivergence.

Social and Emotional Connections

Social experiences:

Living with OCD can sometimes make social interactions harder. The time and energy spent managing anxious thoughts or rituals can leave people feeling isolated or misunderstood—similar to what others across the neurodivergent spectrum may experience.

Co-occurring conditions:

It’s also common for OCD to exist alongside autism or ADHD. While each condition has its own origins, they can share traits like restlessness, distractibility, and difficulty concentrating.

A shared sense of identity:

Many people with OCD describe feeling “wired differently.” For some, this becomes a source of self-understanding that their brain simply works in its own, deeply human way.

Co-occurrence with Other Neurodivergent Conditions

Studies suggest that around one in ten people with OCD also have ADHD, with rates reaching one in four in children. The connection between OCD and autism is also well recognised-findings vary, but research indicates that anywhere between 5% and 37% of autistic children and young people experience OCD.

Similarly, about a quarter of young people with OCD also happen to be autistic. These overlaps highlight that neurodivergence rarely fits into clear boxes; many people experience different traits that shape how they think, feel, and move through life.

Autism and OCD

Co-occurrence with OCD is well documented; overlap often includes repetitive rituals, intense need for predictability, and sensory sensitivities.

Key distinction: autistic routines/rituals are usually soothing or organising, whereas OCD compulsions are anxiety-driven (performed to neutralise intrusive thoughts). Practical tip: assess function and intent of a behaviour before planning support.

ADHD

ADHD and OCD can appear together, creating a push-pull between impulsivity/inattention (ADHD) and perfectionism/over-control (OCD). Presentation may include time loss (compulsions) plus task initiation difficulties (ADHD), which can be misread as “non-compliance.”

Support needs often blend structure + flexibility: short, stepwise plans; visual cues; low-friction routines.

Tourette Syndrome

Strong, well-known links with OCD; some people experience “tic-related OCD.” Overlap may include sensory “just-right” feelings, symmetry/ordering, and touching or repeating behaviours.

Support focuses on anxiety regulation, habit-reversal/competing responses, and low-stimulus spaces when needed.

Learning Disabilities

People with Down syndrome can also experience Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD), which may appear as strong attachment to routines, repetitive behaviours, or a deep need for things to stay the same.

While OCD is less common in people with Down syndrome than in the general population, when it does occur, it can have a noticeable impact on daily life and is often linked with feelings of anxiety. Support usually involves gentle guidance, clear structure, and attention to the sources of stress that may be contributing to these patterns.

Sensory Processing Disorder

OCD and Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD) can appear together, as many people with OCD experience heightened sensory sensitivities that may increase anxiety or become part of their obsessive thoughts.

Some people with SPD show behaviours that can resemble OCD. Although sensory differences aren’t a symptom of OCD itself, they can make obsessive thoughts and compulsions feel stronger, and some people describe “sensory sensations” or a sense of incompleteness as part of their OCD experience.

Understanding, Support and Treatment

People with OCD require bespoke, person-cnetred care that truly understands the person and their needs, desires, dreams and fears. There are a number of ways to effectively support a person with OCD, including:

- Bespoke therapy and personalised care plans – designed around each person’s unique experiences, communication style, and goals.

- Multidisciplinary approach – bringing together professionals who share knowledge and insight to build a full picture of support.

- Positive Behaviour Support (PBS) – focusing on understanding behaviour, reducing anxiety, and promoting meaningful engagement.

- Occupational Therapy – helping people rebuild confidence, independence, and daily structure through purposeful activity.

- Speech and Language Therapy (SALT) – supporting communication, emotional expression, and understanding.

- Trauma-Informed Care – creating safety and trust while recognising the emotional impact of past experiences.

- Family and Carer Collaboration – ensuring consistent understanding and compassion across all parts of a person’s life.

- Psychological Therapies (CBT and ERP) – helping people gradually face fears, develop new coping skills, and regain balance.

- Medication Management – when appropriate, guided by psychiatrists or GPs to reduce distress and support therapy.

- Mindfulness and Emotional Regulation Strategies – teaching calm, grounding techniques for managing anxiety.

- Peer and Community Support – connecting with others who understand the journey to reduce isolation and build hope.

- Environmental Adaptations – making spaces calmer, predictable, and more supportive of wellbeing.

- Collaborative Services:

- PALMS – Positive Behaviour, Autism, Learning Disability, and Mental Health Service

- SCAAND – Service for Complex Autism & Associated Neurodevelopmental Disorders

- CAMHS – Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services

Caring for someone with OCD means seeing beyond the surface of their routines and fears-it’s about understanding the person beneath the anxiety. Many people also live with mental health challenges like mood disorders, which can intensify how OCD feels and how hard it is to find peace.

But with patience, compassion, and the right mix of professional and emotional support, managing OCD symptoms becomes part of a larger journey-one where hope, healing, and self-understanding grow stronger each day.

At the beginning of his support journey, Vladan was nonspeaking and needed structured, consistent support with communication, personal care, and daily routines. Living with autism, a learning disability, and OCD, he required a care approach that understood his unique way of interacting with the world. First, our multidisciplinary team completed a comprehensive assessment. Support workers, education specialists, occupational therapists, and healthcare professionals worked together to design a person-centred plan focused on Vladan’s strengths, interests, and communication needs. Read more.

Promoting Acceptance and Inclusivity

Acceptance and inclusivity need to be present in every part of life-at work, in education, and across our communities. Society needs to build spaces where everyone feels safe to be themselves, understood for their differences, and valued for their strengths.

- Workplaces need to recognise and adapt to different ways of thinking, communicating, and managing routines, creating spaces where people can contribute with confidence.

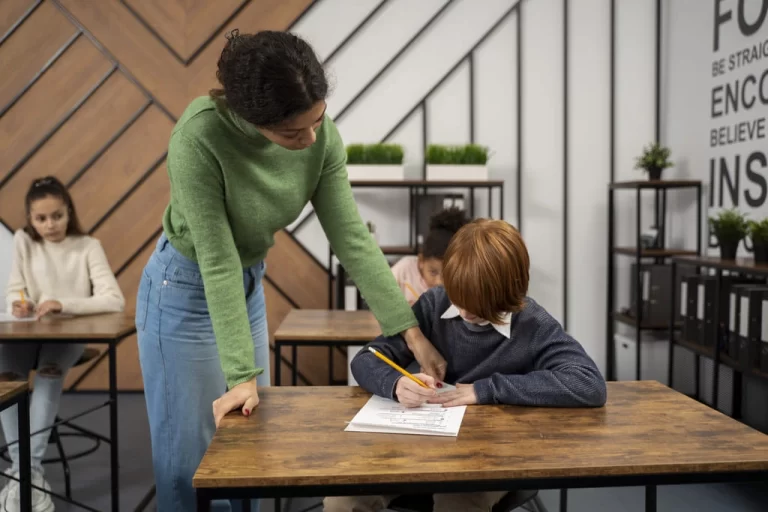

- Schools have a responsibility to understand varied learning styles and emotional needs, ensuring every student feels supported and seen.

- Communities can create belonging by offering understanding instead of judgement, making sure no one feels excluded because of how their mind works.

- Everyday life thrives when kindness, awareness, and patience guide how we relate to one another.

Catalyst Care Group Supports Neurodivergent People

At Catalyst Care Group, we understand that neurodivergent people experience the world through a blend of developmental, neurological, and environmental factors. Conditions such as OCD, autism, ADHD, and learning disabilities often share overlapping symptoms, including sensory sensitivities, repetitive patterns, or challenges with emotional regulation. Recognising these connections allows our teams to provide support that is personal, compassionate, and built around each person’s strengths and needs.

Our support involves collaboration across a wide network of professionals and therapeutic practices:

- Multidisciplinary Team (MDT): A collaborative network ensuring every aspect of support is aligned and person-centred.

- Community Psychiatric Nurses (CPNs): Providing emotional and mental health guidance within the community.

- Mental Health Nurses and General Nurses: Offering both clinical care and emotional reassurance.

- Positive Behaviour Support (PBS): Understanding behaviour through compassion, reducing anxiety, and promoting positive engagement.

- Occupational Therapy (OT): Helping people rebuild confidence, daily structure, and independence through meaningful activities.

- PROACT-SCIPr-UK®: Including proactive, rights-based approaches that focus on safety, dignity, and least-restrictive support.

- Multimedia Specialists: Enhancing communication and understanding through creative, accessible visual tools.

If you’re looking for a personalised, tailored support for people with OCD and other neurodevelopmental differences, get in touch with us today.