In the UK, the Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLS) exist to protect adults who lack mental capacity from being unlawfully restricted as part of their care. They ensure that any limits on a person’s freedom in a care home or hospital are legally authorised, necessary for safety, the least restrictive option available, and in the person’s best interests.

Any restriction on freedom must be justified, lawful, and respectful of the person as a human being – not just a set of risks to manage.

A deprivation of liberty is identified when someone is under continuous supervision and control and is not free to leave. Although DoLS are being replaced by the Liberty Protection Safeguards (LPS), the underlying principle remains the same: a person’s liberty can only be removed through strict legal safeguards, with the Court of Protection responsible for authorising cases outside hospitals and care homes.

In England and Wales, more than 300,000 people are deprived of their liberty through care arrangements, yet meaningful protection of their human rights is still lacking.

When a loved one is subject to restrictions on their freedom, understanding their rights can help families know what to expect and what safeguards should be in place.

Below is a brief overview of Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLS), designed to help families understand when these safeguards apply, how decisions are authorised, and how dignity, choice, and legal protections should be upheld when liberty is restricted.

What Are Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLS)?

Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLS) are an addition to the Mental Capacity Act 2005 and apply only in England and Wales. They exist to protect people who lack the capacity to consent to their care or treatment in a hospital or care home when those arrangements restrict their freedom.

This can include restrictions such as:

- Limits on where a person is allowed to go or who they can see

- Having daily routines, activities, or schedules decided by others

- Being under continuous or close supervision

- Not being free to leave a setting without permission or support

- Restrictions on contact with family or friends

- Decisions about care, treatment, or living arrangements are being made on the person’s behalf

Under DoLS, care arrangements must be carefully assessed to make sure they are necessary, proportionate, and in the person’s best interests. The safeguards also ensure that people have proper representation and a clear right to challenge any deprivation of liberty, helping to protect their rights and dignity.

Key points to understand:

- The Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLS) are part of the Mental Capacity Act and apply only in England and Wales.

- The Mental Capacity Act allows restraint and restrictions, but only when they are necessary, proportionate, and in a person’s best interests.

- When restrictions go further and amount to a deprivation of liberty, additional legal protections are required. These protections are known as the Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards.

- DoLS can be used only when a person is deprived of their liberty in a hospital or care home. In all other settings, authorisation must come from the Court of Protection.

- Hospitals and care homes must apply to the local authority for permission to deprive a person of their liberty. This is known as requesting a standard authorisation.

- Before a standard authorisation can be granted, six separate assessments must be completed.

- If authorisation is approved, a key safeguard is the appointment of a representative with legal authority to support and speak up for the person. This is called the relevant person’s representative and is usually a family member or friend.

- Additional safeguards include the right to challenge the authorisation through the Court of Protection and access to support from an Independent Mental Capacity Advocate (IMCA).

Together, these measures help define when care arrangements move beyond support and into a deprivation of liberty, ensuring they are recognised, reviewed, and properly safeguarded under DoLS.

Why were DoLS introduced?

DoLS were introduced in April 2009 to address a legal gap in how the rights of people who lack mental capacity were protected when their liberty was restricted in hospitals or care homes. Before DoLS, there was no clear legal process to authorise or challenge situations where people were kept under continuous supervision and control without being free to leave, even when this was done for their care or safety.

This issue was highlighted by the Bournewood case, in which the European Court of Human Rights ruled that such arrangements breached the right to liberty under human rights law if they lacked proper safeguards.

In response, DoLS were created to provide a clear, lawful framework requiring independent assessments, formal authorisation, representation, and rights of review and challenge, ensuring that any deprivation of liberty is necessary, proportionate, and in the person’s best interests.

Who Decides if Someone is Being Deprived of Their Liberty?

Deciding whether someone is being deprived of their liberty follows a clear legal process, rather than being left to individual staff or services. In hospitals and care homes, this decision is made by the local authority, acting as the supervisory body under the Mental Capacity Act.

If care arrangements are likely to restrict a person’s freedom, the hospital or care home must ask the local authority for authorisation. Independent professionals then carry out a series of assessments to carefully consider whether the arrangements meet the legal criteria.

When care is provided outside a hospital or care home, decisions about deprivation of liberty are made by the Court of Protection. This ensures that any restrictions on a person’s freedom are properly reviewed, lawful, and respectful of their rights.

Who DoLS Apply To?

DoLS apply to people who may need additional legal protection because their care arrangements place significant restrictions on their freedom. The safeguards help make sure these situations are recognised, authorised, and regularly reviewed.

DoLS may apply to people who:

- Are aged 18 or over

- Lack mental capacity to consent to their care or treatment arrangements

- Are living in a hospital or care home

- Are under continuous supervision and control

- Are not free to leave the setting

This can include people with:

- Mental health needs

- Learning disabilities

- Autism

- Dementia or cognitive impairments

- Acquired brain injuries

- Complex physical or neurological conditions

DoLS exist to ensure that people in these situations are supported in ways that respect their rights, dignity, and well-being.

Situations That May Trigger DoLS

DoLS may need to be considered when care or support arrangements place ongoing restrictions on a person’s freedom, particularly where these restrictions are part of everyday care and the person is unable to consent to them. These situations often arise gradually and with good intentions, which is why recognising when safeguards are needed is so important.

Locked Doors and Constant Supervision

This situation arises when a person is under continuous supervision and is not free to leave their living environment. Example: A person living in a care home is unable to leave the building because exit doors are locked, and staff must always accompany them if they go outside, even though this is done to keep them safe.

Even when these arrangements are put in place with care and good intentions, they can still significantly limit a person’s freedom and may mean that DoLS need to be considered.

Restrictions on Movement or Activities

This applies when a person’s ability to move freely or take part in everyday activities is limited as part of their care arrangements.

Example: A person is not allowed to access certain areas of the care home, go outside independently, or choose activities they enjoy, and must follow a set routine decided by others.

When restrictions like these are part of everyday care and the person is unable to consent, they may indicate a deprivation of liberty and should be properly reviewed under DoLS.

Use of Medication to Control Behaviour

This applies when medication is used by health professionals primarily to manage or control a person’s behaviour, rather than to treat a medical condition.

Example: A person is given medication that makes them drowsy or less responsive to reduce distress or prevent certain behaviours, which in turn limits their ability to move freely, make choices, or leave the setting.

When medication has the effect of significantly restricting a person’s freedom and the person is unable to consent, this may amount to a deprivation of liberty and should be considered under DoLS.

One-to-One Supervision

This applies when a person is supported by health professionals or care staff on a one-to-one basis at all times to monitor their safety or behaviour.

Example: A person is always accompanied by a member of staff, including during personal activities or when moving around the setting, and is unable to spend time alone or leave independently.

When constant one-to-one supervision significantly limits a person’s freedom and they are unable to consent, it may indicate a deprivation of liberty and should be considered under DoLS.

What Is Not Considered a Deprivation of Liberty?

Not every restriction or safety measure in care amounts to a deprivation of liberty. Under the law, there must be continuous supervision and control, and the person must not be free to leave for a situation to be legally recognised as a deprivation of liberty under DoLS. If care involves some supervision or restrictions but these do not reach this level, or if the person has capacity and agrees to the arrangements, then DoLS would not apply.

This is not usually considered a deprivation of liberty when:

- The person can leave freely without being stopped or prevented

- Supervision or help is occasional, proportionate, and part of normal care

- Restrictions are temporary or situational, such as for a specific medical procedure

- The person has capacity and has agreed to the care or restrictions

- Care is provided in a way that minimises restrictions wherever possible

In these situations, care may still involve support and safety measures, but it does not meet the legal threshold of continuous control and lack of freedom that triggers DoLS.

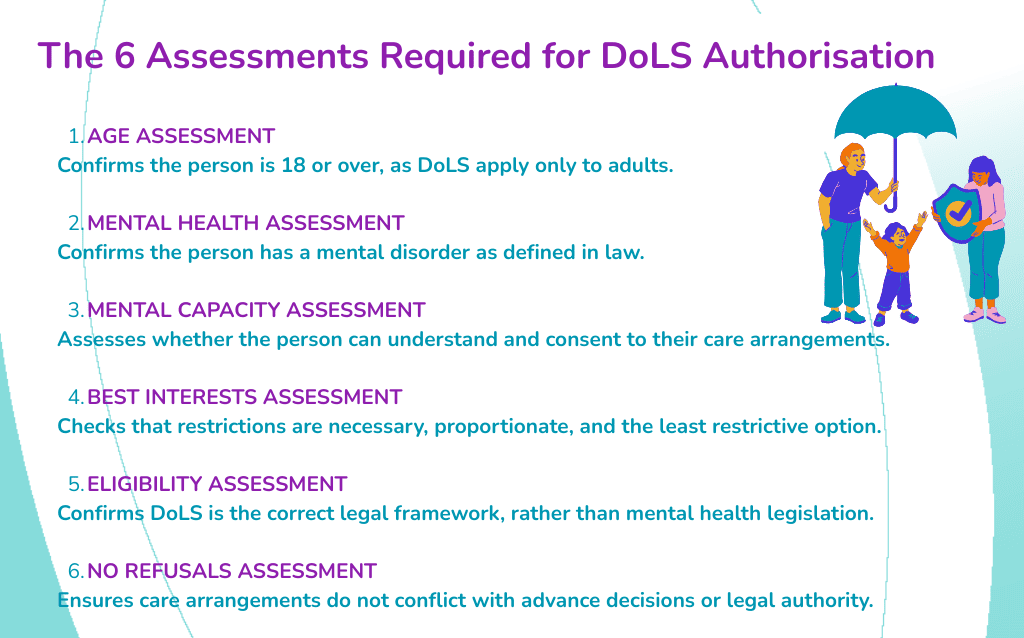

The Six Assessments Required for DoLS Authorisation

Before a Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLS) authorisation can be granted, the law requires a clear assessment process to make sure a person is being protected, not unlawfully restricted. These assessments confirm whether the person lacks capacity, whether restrictions such as physical restraint or continuous supervision are necessary, and whether the situation fits within the legal framework of the Mental Capacity Act. Together, they help prevent unlawful deprivation of liberty and ensure decisions are made fairly and lawfully.

Each assessment is carried out by trained professionals, including a mental health assessor, and focuses on a specific legal requirement.

- Age Assessment – This confirms that the person is 18 years or older, as DoLS only applies to adults. If the person is under 18, different legal protections must be used.

- Mental Health Assessment – A mental health assessor checks whether the person has a mental disorder as defined in law. This does not require a diagnosis alone but confirms that the legal criteria for DoLS are met.

- Mental Capacity Assessment – This assessment considers whether the person is able to understand, retain, weigh up, and communicate a decision about their care or living arrangements. DoLS can only apply if the person lacks capacity to consent to these arrangements.

- Best Interests Assessment – This assesses whether the care arrangements, including any restrictions or physical restraints, are necessary, proportionate, and in the person’s best interests. It also considers whether there are less restrictive alternativesthat could meet the person’s needs.

- Eligibility Assessment – This determines whether DoLS is the appropriate legal framework or whether the situation falls under mental health legislation. Only one legal framework can apply at a time.

- No Refusals Assessment – This checks that the proposed care arrangements do not conflict with any valid decisions already made by the person, such as an advance decision, or with decisions made by someone holding legal authority on their behalf.

Rights of the Person Subject to DoLS

When a person is subject to the Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards, the law is clear that their rights must remain protected and visible, even where restrictions are considered necessary. DoLS are not about removing rights, but about making sure any loss of liberty is lawful, proportionate, and open to challenge within the legal framework of the Mental Capacity Act.

A person subject to DoLS has the right to:

- Be informed

The person, and those close to them, must be told that a DoLS authorisation is in place and what it means, in a way that is clear and accessible. - Challenge the authorisation

The person, or someone acting on their behalf, can challenge the DoLS authorisation through the Court of Protection and seek legal advice if they disagree with the restrictions. - Access an Independent Mental Capacity Advocate (IMCA)

If the person does not have family or friends to support them, they are entitled to an IMCA, who helps ensure their views, wishes, and rights are represented. - Have regular reviews

DoLS authorisations must be reviewed regularly to check whether the restrictions are still necessary or whether less restrictive arrangements are possible. - Be protected by the correct legal framework

The person has the right to be supported under the appropriate law. If detention or treatment is primarily for mental health reasons, the Mental Health Act may apply instead of DoLS, but only one framework can be used at a time.

These rights exist to make sure people are not quietly or indefinitely restricted, and that their voice, dignity, and legal protections remain central throughout their care.

The Role of Care Providers

Care providers are often the first to notice when everyday support starts to place real limits on a person’s freedom. Their role is to recognise when care arrangements go beyond support and begin to restrict liberty, and to make sure the right protections are put in place at the right time.

This means raising concerns early, requesting authorisation when needed, and continuously checking that care remains necessary, proportionate, and as flexible as possible, with the person’s rights and wellbeing guiding every decision.

How Care Providers Can Stay Compliant

Staying compliant means making sure care is delivered in a way that is safe, fair, and respectful of a person’s freedom. This goes beyond policies and paperwork. It relies on clear team policies, a culture where a person’s life, dignity, and freedom are considered in every action and interaction, and where well-being is always kept at the forefront of care.

- Training and awareness – making sure staff understand what DoLS are, when they apply, and how everyday care can sometimes limit a person’s freedom

- Documentation and record-keeping – clearly recording care decisions, support plans, and the reasons behind any restrictions, so families and professionals can understand what is happening and why

- Regular reviews and audits – checking care arrangements often to make sure restrictions are still needed and are not being used for longer than necessary

- Embedding least restrictive practice – always looking for safer, more flexible ways to support people, asking whether restrictions can be reduced or removed while still keeping the person safe

DoLS and Restraint: What’s the Difference?

DoLS and restraint are closely linked but not the same thing. Restraint refers to specific actions used to limit a person’s movement or behaviour, such as physical holds, restricting movement, or using medication to reduce distress, and it may be lawful if it is necessary and proportionate to prevent harm. DoLS, however, looks at the overall care situation.

It applies when restrictions and supervision, taken together and over time, mean a person is under continuous control and not free to leave. In simple terms, restraint is about what is done, while DoLS is about the wider impact on a person’s freedom.

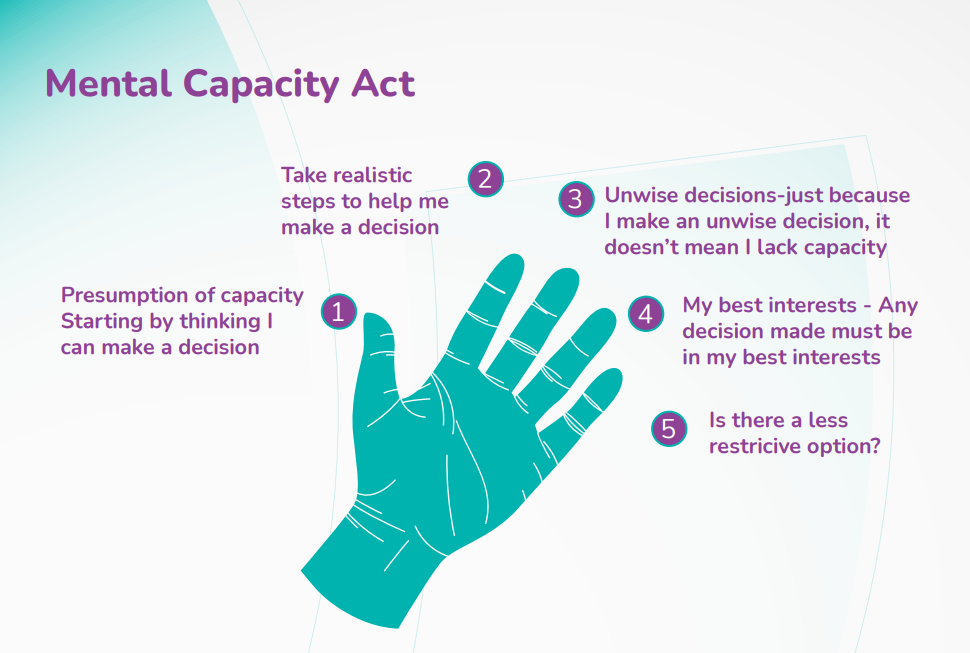

Mental Capacity Act and Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards

The Mental Capacity Act provides the legal framework for supporting people who may be unable to make certain decisions for themselves. It sets out how capacity should be assessed, how decisions must be made in a person’s best interests, and the importance of choosing options that restrict freedom as little as possible.

The Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLS) sit within this framework and apply when care in a hospital or care home places significant limits on a person’s freedom. DoLS introduce additional protections, including independent assessments, formal authorisation, regular reviews, and the right to challenge decisions, ensuring that any loss of liberty is lawful, necessary, and respectful of the person’s rights and dignity.

How Do DoLS Protect Vulnerable Adults?

DoLS protect vulnerable adults by ensuring that any serious restrictions on a person’s freedom are noticed, questioned, and legally authorised, rather than occurring quietly or without oversight. When someone lacks mental capacity and is under continuous supervision and unable to leave, DoLS require independent assessments to verify that the arrangements are necessary, proportionate, and in the person’s best interests.

They also guarantee important rights, including the right to representation, regular reviews, and the ability to challenge decisions. These protections are rooted in the Mental Capacity Act and reflect wider human rights principles.

Over time, DoLS are being replaced by the Liberty Protection Safeguards (LPS), which aim to strengthen and streamline these protections across more care settings, while keeping the same core focus on safeguarding people’s liberty, dignity, and well-being.

Can Deprivation of Liberty Be Prevented?

In many cases, deprivation of liberty can be prevented if social care professionals design and review care plans to avoid meeting the legal thresholds of continuous supervision and control and a lack of freedom to leave. This requires careful, proactive planning rather than reacting once restrictions are already in place.

Prevention is most likely when:

- Supported living care plans are genuinely personalised and flexible, rather than mirroring care-home models

- Social care professionals actively test whether restrictions are necessary, or simply routine practice

- Support is arranged in the least restrictive way, balancing safety with choice, privacy, and independence

- People are supported to leave their home freely, with assistance if needed

- Supervision is proportionate and risk-based

If restrictions cannot be reduced and the care plan still amounts to a deprivation of liberty, the law is clear that a Court of Protection application must be made to authorise this lawfully. The safeguard, in this case, is not avoiding authorisation, but ensuring that the restriction is properly scrutinised, time-limited, and regularly reviewed, so that a person’s liberty is restricted only where there is no realistic alternative.

This is why good practice focuses first on prevention through least-restrictive care planning and only turns to court authorisation when that threshold cannot safely be avoided.

Catalyst Care Group Provides Proactive, Least Restrictive Support Strategies

At Catalyst Care Group, care is delivered through a person-centred and integrated approach, grounded in a strong human-rights model of care. Using Positive Behaviour Support (PBS) strategies, teams are equipped to respond effectively during periods of distress, support stable transitions, and reduce avoidable hospital admissions. As a certified PROACT-SCIPr-UK® training centre, teams are supported to develop the skills needed to provide thoughtful, compassionate support for people whose behaviour may present challenges.

Support plans are carefully designed with proactive strategies that focus on reducing the need for reactive and restrictive interventions. This approach is strengthened through access to a broad range of specialist services, including occupational therapy, speech and language therapy, mental health support, and multimedia support.

Working as part of a multidisciplinary team that includes PBS specialists, community psychiatric nurses, and in collaboration with the Restraint Reduction Network, we focus on achieving the best possible outcomes for people. This approach includes:

- Carrying out functional and purposeful assessments of behaviours of concern

- Following a structured risk assessment process

- Developing evidence-based support strategies

- Providing regular, personalised training for support teams

- Creating tailored PBS plans shaped around people’s needs

- Working collaboratively across multiple disciplines

- Supporting staff emotionally and encouraging open, reflective conversations

Aligned with Building the Right Support and rooted in a human-rights approach, Catalyst Care Group works alongside colleagues across health and social care sector to enable people to receive high-quality, person-centred support within their own homes and communities.

For more information, contact us today.

FAQs

What to do if someone is deprived of their liberty?

If a person who lacks mental capacity is being deprived of their liberty outside a care home or hospital, you must go to the Court of Protection to get a legal order authorising that restriction of freedom. To do this, you start the process by completing the Application to Authorise a Deprivation of Liberty form – COPDOL11 – which is used for seeking the court’s authorisation in community or other non-institutional settings.

What happens after a deprivation of liberty is authorised?

After a deprivation of liberty is authorised, the person is still protected. Someone is appointed to look out for them and help make sure their rights are respected. The authorisation is only in place for a set period of time, and it can be looked at again whenever things change or concerns are raised.

What is the maximum length of DoLS?

A deprivation of liberty should only be in place for as long as it is genuinely needed, and never for more than 12 months. Throughout this period, the person’s representative should be kept informed about their care, treatment, and any changes to the arrangements.